Author Q&A: Ben Dolnick

September 18, 2020

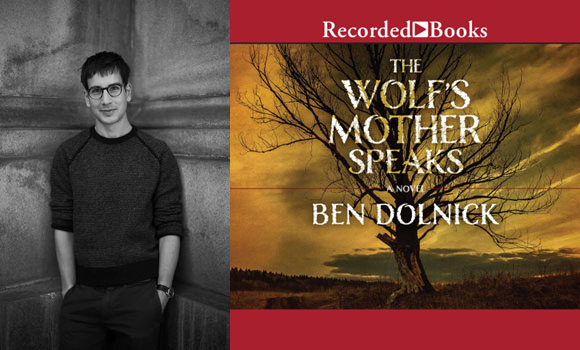

(Photo Credit: Todd Heisler)

In The Wolf’s Mother Speaks, Ben Dolnick takes listeners on an unforgettable, hauntingly funny journey alongside a mother whose love takes many forms. A mother (Joyce) finds out a secret about her estranged adult son, namely that he regularly turns completely into a wolf. No, not a werewolf half-man half-wolf creature, but a full-on actual wolf. It’s out of his control when it happens, and he’s done some terrible things. Once Joyce finds out, she goes to great lengths to help her beloved son. But as the novel unfolds, the narrative explores ideas not only of survival and murder and familial devotion in the face of the most challenging and unbelievable circumstances, but also of mental illness if not actual insanity. The result is a thrill ride with a lot of bumps and a substantial body count.

We were thrilled to “sit down” with Ben to talk about his new audiobook—download coming September 29, 2020!

Author Q&A: Ben Dolnick

Recorded Books (RB): In The Wolf’s Mother Speaks, the main character Joyce is dealing with a painful estrangement from her son, which seems very realistic, and then things take a turn into the supernatural. Where did the inspiration for The Wolf’s Mother Speaks come from?

Ben Dolnick: I think the first inkling I had of this book was when, years ago, I read a story about a serial killer being arrested at his house in Kansas. This was one of those situations in which the killer has a wife, a family, neighbors who think they know him, the whole domestic scene. And I was so fascinated, particularly by his family members — what did they know? What did they think of him now?

But I knew that I didn’t want to write a standard serial killer book — I love a good serial killer novel (Red Dragon is one of the more compelling books I’ve ever read), but I didn’t want to write something with forensics, FBI agents, etc; I was after something weirder.

So, I handed those inputs — some murder, some family dynamics, some strangeness — to the mysterious mental organ where novels gestate, and out popped this book!

RB: Was the writing process different for this book from how it was for your previous novels (The Ghost Notebooks, Zoology, You Know Who You Are, and At the Bottom of Everything)?

Ben: This was a much more “spoken” book than those — which is to say that the vast majority of the book is actually purporting to be transcribed speech. That made this book lots of fun to write — I love nothing more, as a writer, than doing various voices — but it also made for various narrative challenges. People tell stories very differently than they write them — there was no room for literary tricks, or elegant descriptions, or anything like that. It’s a much more compact and slangy sort of writing.

RB: You’re an avid audiobook listener, which we love to hear! What is it about audiobooks that speaks to you, both in your personal listening, and as a writer?

Ben: Yes, audiobooks are the best! I’ve always thought of writing, despite the silence in which it takes place, as fundamentally an auditory medium. When I walk into a library where everybody’s quietly reading in their little carrels or whatever, I see it like one of those weird silent raves, where everybody’s wearing headphones and quietly thrashing around in ecstasy. This person is hearing Vonnegut, this person is hearing Toni Morrison, this person is hearing Murakami — and all that hearing is taking place entirely internally.

So audiobooks just make that aural quality of writing even more tangible. I spent a lot of the quarantine so far — 55 hours of it, in fact! — listening to War and Peace, and I don’t think I could have gotten through it, certainly not with such pleasure, if I had just been reading it. Each character, however long it had been since I’d heard from them, was immediately identifiable by their voice. It felt even more intimate than reading, in a way. My eyes can skim or rush in a way that my ears usually don’t.

RB: What was it like hearing your previous novels in audiobook form for the first time?

Ben: It was amazing! I was so used to hearing the books in my head — by the time a book is published, you can all but recite it — but here it was actually taking form in space, in the sound of a stranger’s voice. And it was fascinating to hear the little choices the readers made, both at the sentence-level and in terms of character. It was kind of a bittersweet thing, like (I imagine) watching a kid go off to college — you’ve worked so hard on this thing and off it goes to lead an independent existence, no longer under even the illusion of your control.

RB: What do you personally like to read or listen to?

Ben: Everything! Lately I’ve been listening to classics — I’m moved onto Proust, after finishing War and Peace — but I also listen to lots of Buddhist stuff (Already Free by Bruce Tift is a recent favorite). And reading-wise I’m all over the place. I read a lot of thrillers — police procedurals (Ed McBain is great), supernatural stuff (Dracula, Frankenstein), espionage (Eye of the Needle is truly amazing). Lately I’ve been reading some more experimental fiction — Perec’s Life: A User’s Manual, a bunch by Mark Leyner, some Gerald Murnane. My bedside table is basically a perpetual avalanche of things I’m halfway through.

RB: If you could curate a shelf for The Wolf’s Mother Speaks to sit on, what other books would be on it?

Ben: It would have to be an eccentric shelf! I think I’d love to put it somewhere between the funny, experimental, voice-obsessed books of, say, George Saunders and David Foster Wallace, on one side — and then on the other side I’d like to have the plotty, efficient novels of Ira Levin (Rosemary’s Baby, Stepford Wives, etc.). Oh, and let’s put some Alice Munro on that shelf too! She is hands-down the best at all things related to families — and she’s got quite a way with plot too. That would be a shelf where my book would live very, very happily.

RB: What’s your favorite scary story?

Ben: I think Ira Levin’s The Boys from Brazil is my favorite of the moment. It’s tense and strange and brilliantly told. The whole last third — which I feel like I can’t describe at all without spoiling it — is just hilariously compelling. He’s able to do that Hitchcock thing of making you hold your breath for minutes at a time while the characters walk a tightrope over a flaming pit.