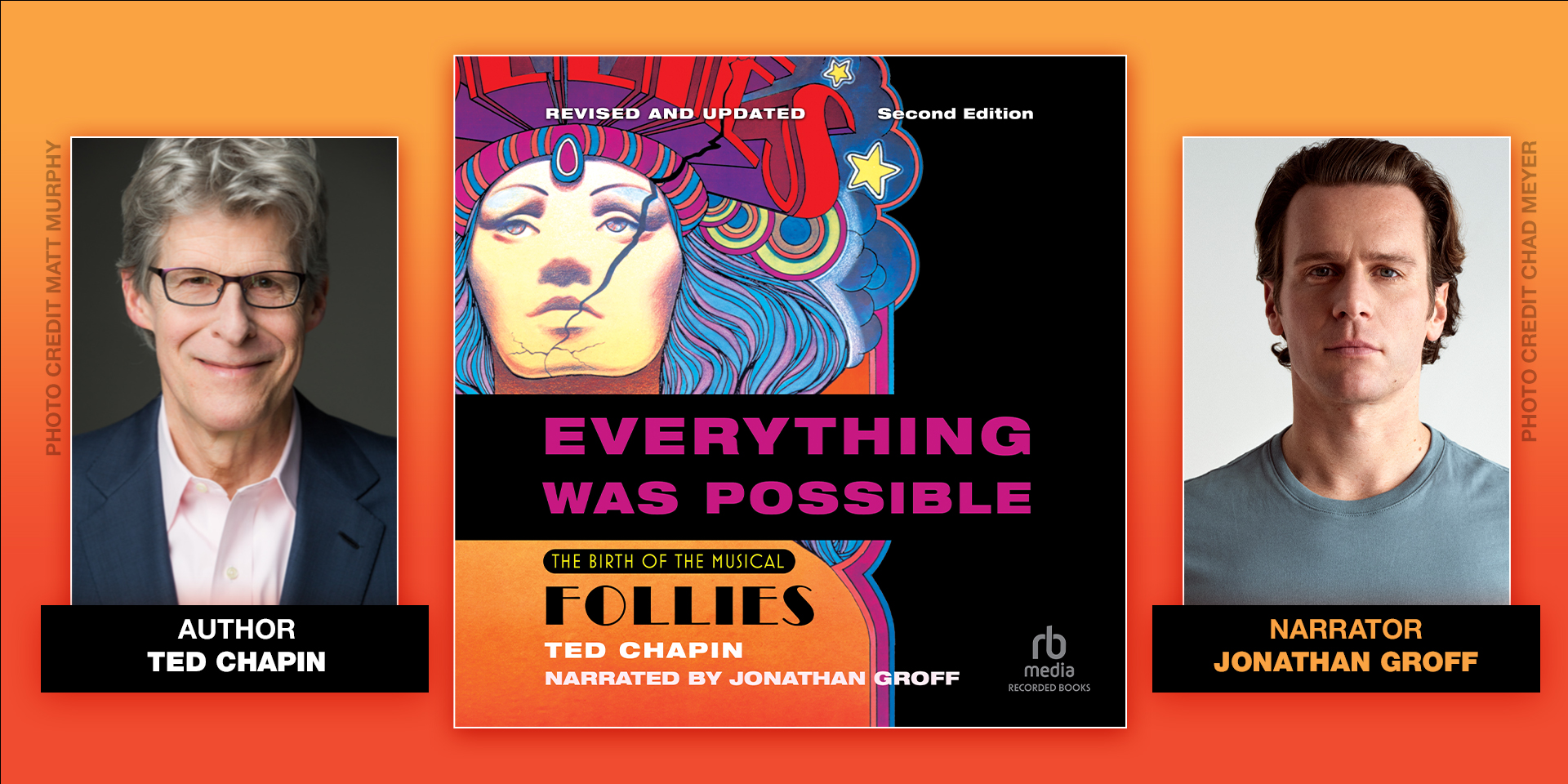

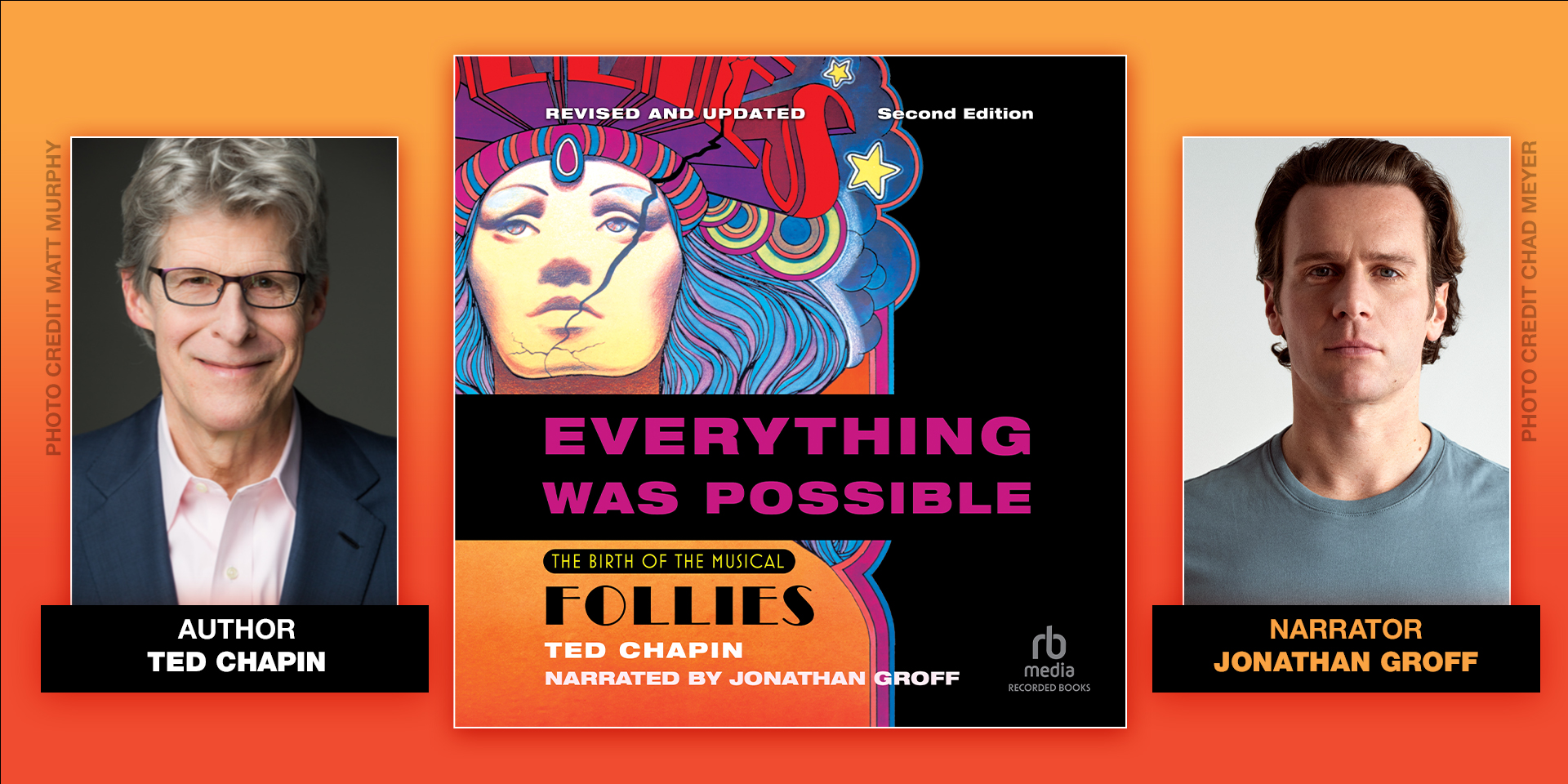

Jonathan Groff interviews EVERYTHING WAS POSSIBLE author Ted Chapin

August 30, 2022

In 1971, college student Ted Chapin found himself front row center as a production assistant at the creation of one of the most beloved Broadway musicals, “Follies.” Needing college credit to graduate on time, he kept a journal of everything he saw and heard and thus was able to document in extraordinary detail how a musical is created.

Now more than 50 years later, Ted has created an out-of-this-world chronicle. “Follies” was created by Stephen Sondheim, Hal Prince, Michael Bennett, and James Goldman, now icons of the Broadway industry, but at the time just building their reputations.

Ted recently sat down for a discussion with the narrator, Jonathan Groff, known for his own performances on screen, stage, and television. Jonathan has appeared in productions such as “Hamilton” and “Spring Awakening”, along with television and film appearances in “Glee,” “The Matrix,” and “Frozen.”

Learn more about the audiobook, available everywhere audiobooks are sold.

Jonathan: Why an audiobook now and what inspired it? And I’m so happy that it took 20 years to happen because we’ve become friends during that time. Now I got to read it, which was a great, great pleasure, an extreme pleasure that I can speak in more detail about, but why now? Why the audiobook now?

Ted: Well, it’s as simple as my agents saying, “Hey, we never did an audiobook. Let’s see if there’s an interest.” To which I said, “Why not?” And then of course was like, well, who should read it? And I said, well, um, you know, I have a suggestion of somebody who is a friend, but on his own, you know, is more than capable and does some of these books. So, Jonathan Groff and here we are. So I’m thrilled. I’m thrilled that you ended up doing it.

J: There’s just something so moving about the way that you describe the experience from your perspective and these actors that are of a certain age, coming together and kind of, like, laying everything on the line. And your spirit — I felt so connected to you <laugh> in so many ways because I never went to college and I learned everything about acting by watching and being in the ensemble of shows. And my first Broadway show, I was an understudy in a swing. And so this perspective that you have of watching from the audience, slash, watching from the wings, I just felt so connected to it because it’s how I learn. I feel like your way in this book is just so specific and so emotional, because it really is like, I feel like the, how old were you when you were 20. I feel like the 20-year-old you when I’m reading it. We kept having to stop in my recording. It was a little embarrassing at first, and then it just kept happening all the time. The amount of time that we had to stop for me, uh, weeping. It was just the weeping that took a little bit longer.

T: <laugh> Well, I love it.

J: Emotional to write. What was it like when it started?

T: Well, it was interesting to dive back into what I had saved. Since I did write it based on a journal that I kept, obviously, and a report that I put together for college. So when the idea of the book came up, I had really no idea what that all was. I hadn’t looked at it in years. When I opened the magic box and dove in, I was surprised at how much was there. It was a very good first step. I think, you know, to your point, and I love hearing you say that it’s, if you don’t love the theater, don’t go into it. <laugh> And I think, you know, because it takes a lot of love, because there’s a lot of not love around. And so, I think what you got from it, which pleased me more than anything is, you know, I loved the idea of being part of the theater. Since I didn’t know exactly where I would fit in the idea of observing, the first job I had was at 16 years old. So that just being there and watching and being fascinated by the personalities as you point out, and this one happened to be a very, very special group of people ranging from the old folk who were nervous to the main creative guys who were all still hungry. It’s a point I always like making that we now say Stephen Sondheim, Hal Prince, and Michael Bennett are gods of the musical theater. At the time they weren’t that; they were on a trajectory. The company had made everybody take a different kind of notice, but the company wasn’t uniformly loved. So, this was the next step. This was another step towards establishing their beach hole or whatever that word should be. As major figures in the musical theater, which of course they were, and working together on this peculiar but absolutely fascinating show.

J: The level of details in this book is so extreme and you paint such a specific picture that I feel like I was there. And is that because you kept those journals that you were able to be so specific? I mean, down to, “it was Tuesday at 3:00 PM and I was in a car with Yvonne [DeCarlo] and we talked,” it’s so meticulous and specific.

T: Well, I did take notes every day after rehearsal, so you know the detail couldn’t have been done otherwise. But what was fascinating when I was writing the book is whenever I’d come up against something like how music was copied or how scripts were done, or the mirror chips on the costumes that were cutting into the arms of the chorus folk. Every time I got to something like that, I thought, “Oh, you know what? I shouldn’t assume the reader knows what I’m talking about.” So if I can do this in a charming way, let me dive in and explain, because I worked very hard to make those hopefully interesting to read. I do find sometimes when people go into detail in books, my mind wanders and I’m off somewhere else. But I just kept trying to do it to serve the story.

J: I think it was a joy to read and even sometimes I would be reading those details and I would start crying <laugh> because it’s not just observational. It feels to me when you’re describing things in such detail that there’s so much love. It’s coming from a place of this 20-year-old having to get it all down because he just loves it so much.

T: Exactly. And oh, the other thing to that is, as you know, the mosaic of putting any show together. Where somewhere in the city, costumes are being built, and somewhere in a museum, orchestrations are being written out, and somewhere lighting plots and lighting instruments are being pulled together. Each of those elements knows what its own timeframe is. Yeah. But it’s all gotta come together at the same time. Yes, and that’s so interesting. Suddenly the costumes arrive, but there’s one missing. Or, you know, suddenly there’s a new song that hasn’t been orchestrated yet. So, you know, it’s all those sorts of curious things.

J: You describe the personalities of the actors, the process of the writing, and the copying. How did you toe the line of being truthful but not too exposing of certain people? Was that something you gave a lot of great care and thought to, and is there anything that you left out that you feel was too private that you’ll always keep for yourself? Or do you feel like you kind of laid it all out on the floor with this one?

T: <laugh> I laid it all out. But I wanted to be as honest as I could. Not hide things but also not be mean. From the very beginning, I didn’t feel that I wanted to get even with anybody, nobody did me wrong. I loved the whole experience.

J: So, what was his [Sondheim] reaction to your book after he read it?

T: When I handed him the manuscript, it was at the time the Kennedy Center was doing the sound festival and he said, “Listen, I’m going down to Washington, I’ll get to it as quickly as I can.” Then a day later I got a message that said, “I started reading it. You got a lot of things wrong. But let me finish it and I’ll give you a call.” And I thought, “Oh great.” So, a few days later he called and he said, “I think this is the best book ever written about the musical theater.”<laugh> I said, “Oh, oh great.” He said, “You got some things wrong at the beginning.” I said “Okay. All right. Just tell me what they are and I’ll fix ’em.” Then he wanted to go through it. So, I went over there, and he had it, page by page. He had some comments, you know, some grammar, punctuation. That’s where he said, “You know, “prickly,” is that your word?” He was great. Hal was great about it too. Hal wrote me a very detailed single-space letter of comments that he had. Yeah. But I figured if I’m gonna write this book, I wanted it as accurate as possible. Why not send it to everybody? John Breglio, who was a lawyer at that time and is still the lawyer for the Michael Bennett estate and was Steve’s lawyer — I sent it to him and he, over a weekend, called me and he said, “I just must tell you that I picked it up on Sunday morning. I was just gonna read a couple of chapters and I couldn’t put it down. I read it all the way through it.” <laugh> I said, “Okay, that’s good. I like that. You know, I’ll take that.”

J: It’s so funny because it really does read like a theater experience. You can’t wait to find out what is gonna happen next.

What is your opinion of the show? Do you feel like you can have an opinion, considering you were so connected to the original, but like looking back or even looking forward, what do you think of the show “Follies?”

T: Of course, as you know, when you’re involved in a show, you lose your perspective. So, you do love it. I do love it and what I find every time I have reason to go back and, you know, dive into it. I find it is so extraordinary in its aspirations of what it’s trying to do. Then when I see productions, I invariably say, oh, wait a minute — I know it says that this takes place in this theater the night before it’s gonna be torn down, but the original production did that in an abstract fashion, which allowed it to be so theatrical there were no chairs and only one table that had food on it. If people perched, it was on rubble, because it looked like it was crumbling. I will hold onto abstraction as being key to making productions. I’ve really loved the original production and have liked some productions, some more than others. I’m a traditionalist. For years I’ve urged somebody, while there’re enough people still around, to remount the choreography, and build those platforms because it was never captured. Michael Bennett said it was his best.

J: I think it has become essential reading for anyone that has anything to do with the theater and beyond, of course, because when a story is told with as much detail as you tell it. I think anybody, in any line of work, can appreciate it and fall in love with it. Definitely for people in the theater, it is required reading. And here it is 20 years later. And Lin, when I was recording it, Lin-Manuel Miranda was FaceTiming me and I told him, “Oh, I’m doing the audiobook of ‘Everything was Possible.'” And he said, “I just reread that two weeks ago.”

T: <laugh> Yeah, he was, when I first met him, he was a big fan. It was great.

J: It really is such a gift because it’s a complete education. It really is such a document of the way things were done. And it’s a document of how things still feel. It’s so rooted in its time period. And so timeless at the same time, in the same moment. It’s so extraordinary in that way, which is very “Follies.” It’s about the past and present at the exact same time.

T: Exactly. And in using both to influence the other, I remember reading a Diane Arbus quote about how the more detailed you are, the more general you are. Don’t be afraid of going into the details because if you try to find a middle ground, it probably won’t work.

J: And the more universal it becomes.